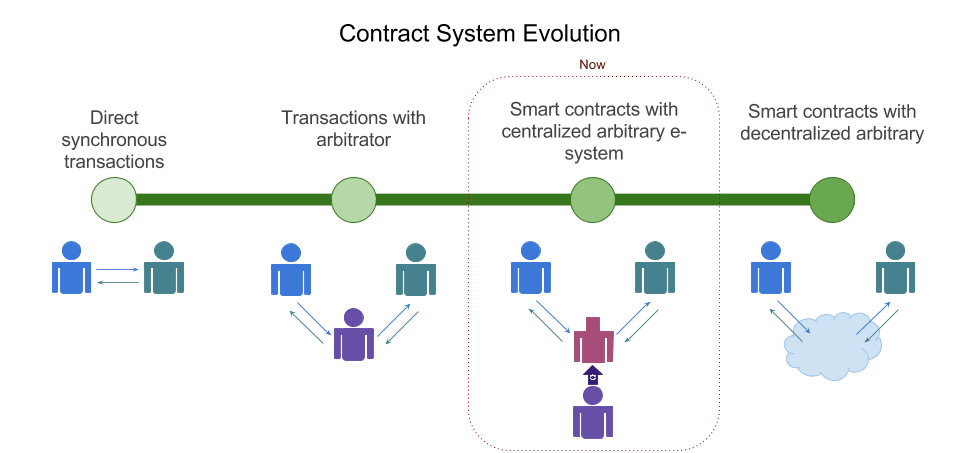

Like many ideas in the blockchain industry, a general confusion shrouds so called ‘smart contracts‘.

A new technology made possible by public blockchains, smart contracts are difficult to understand because the term partly confuses the core interaction described.

While a standard contract outlines the terms of a relationship (usually one enforceable by law), a smart contract enforces a relationship with cryptographic code.

Put differently, smart contracts are programs that execute exactly as they are set up to by their creators.

First conceived in 1993, the idea was originally described by computer scientist and cryptographer Nick Szabo as a kind of digital vending machine. In his famous example, he described how users could input data or value, and receive a finite item from a machine, in this case a real-world snack or a soft drink.

In a simple example, ethereum users can send 10 ether to a friend on a certain date using a smart contract.

In this case, the user would create a contract, and push the data to that contract so that it could execute the desired command.

Ethereum is a platform that’s built specifically for creating smart contracts.

But these new tools aren’t intended to be used in isolation. It is believed that they can also form the building blocks for ‘decentralized applications’ (Dapp) and even whole decentralized autonomous companies (DAO).

How smart contracts work

It’s worth noting that bitcoin was the first to support basic smart contracts in the sense that the network can transfer value from one person to another. The network of nodes will only validate transactions if certain conditions are met.

But, bitcoin is limited to the currency use case.

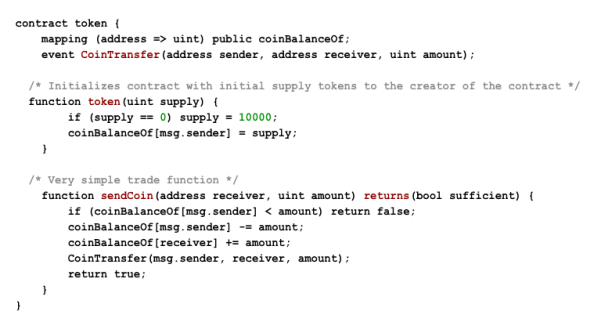

By contrast, ethereum replaces bitcoin’s more restrictive language (a scripting language of a hundred or so scripts) and replaces it with a language that allows developers to write their own programs.

Ethereum allows developers to program their own smart contracts, or ‘autonomous agents’, as the ethereum white paper calls them. The language is ‘Turing-complete’, meaning it supports a broader set of computational instructions.

Smart contracts can:

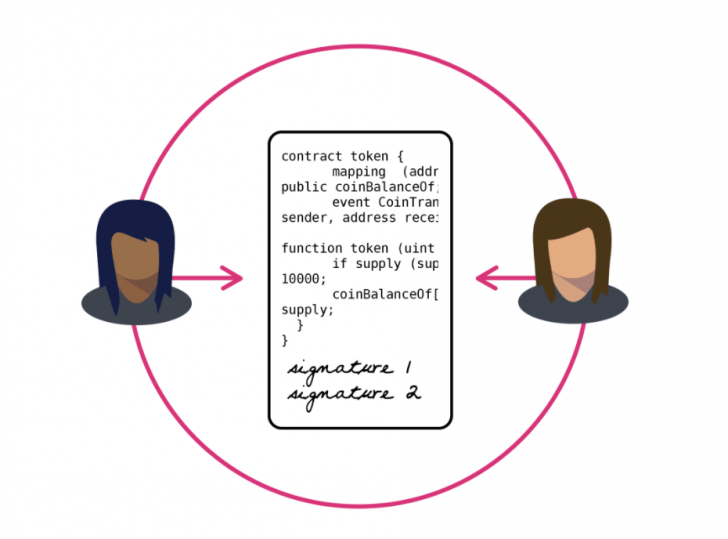

- Function as ‘multi-signature’ accounts, so that funds are spent only when a required percentage of people agree

- Manage agreements between users, say, if one buys insurance from the other

- Provide utility to other contracts (similar to how a software library works)

- Store information about an application, such as domain registration information or membership records.

Strength in numbers

Smart contracts are likely to need assistance from other smart contracts.

When someone places a simple bet on the temperature on a hot summer day, it might trigger a sequence of contracts under the hood.

One contract would use outside data to determine the weather, and another contract could settle the bet based on the information it received from the first contract when the conditions are met.

Running each contract requires ether transaction fees, which depend on the amount of computational power required.

Ethereum runs smart contract code when a user or another contract sends it a message with enough transaction fees.

The Ethereum Virtual Machine then executes smart contracts in ‘bytecode’, or a series of ones and zeroes that can be read and interpreted by the network.

Smart Contracts

A smart contract is some code which automates the “if this happens then do that” part of traditional contracts. Computer code behaves in expected ways and doesn’t have the linguistic nuances of human languages. Code is better, as there are less potential points of contention. The code is replicated on many computers: distributed/decentralised on a blockchain (more on that later) and run by those computers, who come to an agreement on the results of the code execution.

The idea is that you can have a normal paper contract with all the “whereas” clauses that lawyers enjoy, and then a clause that points to a smart contract on a blockchain, saying “this is what we both agree to run and we will abide by the results of the code.”.

The Ethereum Blockchain

Shared ledgers can be useful when you have multiple parties, who may not trust each other fully, each comparing their version of events with each other.

With a smart contract, there is only one set of trade terms, written in computer code, which is much less fluffy than legalese, and agreed upon up-front. The external dependencies (price of oil, share price of Apple, etc) can be fed in via a mutually agreed feed. The contract will live on a blockchain, and run when an event happens or when the bet expires.

Gayle Shaw Jenkins

Developer / Google Partner

Technology Enthusuast. Website & advanced application development and deployment. Want to learn more? Let me know!